Soooo... this is one of the towering achievements of its decade, ja?! If there's one aspect of my taste that particularly stands out to me, it's the fact that I consistently find myself leaning towards the great spiritualist filmmakers for comfort: Bergman, Tarkovsky, Dreyer, Bresson. I didn't realise it before, but having seen Wind I don't think it's too much of a stretch to place Kiarostami alongside those greats (double this up with Taste of Cherry and I'm sold.)

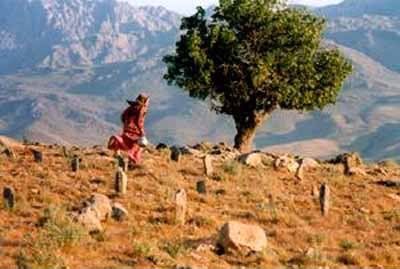

Soooo... this is one of the towering achievements of its decade, ja?! If there's one aspect of my taste that particularly stands out to me, it's the fact that I consistently find myself leaning towards the great spiritualist filmmakers for comfort: Bergman, Tarkovsky, Dreyer, Bresson. I didn't realise it before, but having seen Wind I don't think it's too much of a stretch to place Kiarostami alongside those greats (double this up with Taste of Cherry and I'm sold.)The delicately languorous rhythms of Wind allow the audience to savour every sweet moment of this masterpiece, whilst contemplating the director's deft use of space (which, more than character or plot, is where I derive the bulk of the film's meaning.) Kiarostami's most overt visual tactic is to deploy breathtaking long-shots of the Iranian landscape, which not only acts as a tribute to this naturally ravishing country, but also serves to underline the relationship of character to the world beyond - a world that humbles any pretensions of self-importance by rendering everyone within it an indistinguishable dot against the might of its beauty. But Kiarostami doesn't stop there - he's concerned with matters beyond the physical, and accordingly utilizes an aural dimension that expands his scope considerably: a simple, but effective use of sound that alludes to the expanses outside our frame of vision. His soundtrack seemingly captures the wealth of rural and village life in its entirety, but on more cogent terms it also frequently separates ethereal from corporeal by presenting us with voices that aren't accounted for by on-screen events. Thus, numerous characters are heard but not seen, quietly compelling the viewer to confront the nature of (their?) material existence.

It's within this set-up that we're presented the character of Behzad, our narrative's channel for these concerns. As a possible filmmaker (I don't think it's ever made entirely clear?) he arguably functions as Kiarostami's alter-ego here, whilst his relatively Westernized outlook simultaneously embodies him with the traits of the film's audience. The former role gifts the film with much of its peculiar comicality (the grievances and dubious ethics intrinsic to the filmmaking process), whilst the latter reinforces the distinctly metaphysical concerns at its core. This duality reaches a literal and figurative altitude with a delightful running gag that finds Behzad having to drive to the top of a mountain graveyard in order to perform the cosmopolitan task of answering a mobile phone. Aside from the humour inherent in these trips, the journey is also a curious ascent towards death that metaphorically falls short of reaching Kiarostami's heavenly skies. Implicitly, the phone contributes to the deprivation of Behzad's spiritual self through its inextricable link to his inferred past which, it should be noted, is what provides him with the decidedly inhumane goal of awaiting a village elder's death. The driving force of this narrative then, is the attempt to reconcile those aforementioned divergences between ethereal and corporeal, but within Behzad's character. Kiarostami's typically subtle observations in this regard belie the complexity of Wind's undercurrents, which - for a film that's preoccupied with the idea of death (it's referenced in more ways than I could possibly recount) - ultimately make this one of the most moving paeans to the marvels of human life that I've ever encountered.

No comments:

Post a Comment